Comics and History

Paul Bristow • April 23, 2020

Picturing Yesterday

This post originally appeared on the excellent Scottish History Network blog, but we've shared it again here as it nicely sums up why we do what we do...

Visual storytelling is one of the first ways histories were recorded – from the caves of Lascaux to Sauvet or Sulawesi. We see it too in Trajan’s Column and the Bayeux tapestry. My own personal introduction was reading Charley’s War in Battle comic – in which writer Pat Mills and artist Joe Colquhoun tell the story of an underage soldier in the trenches of the First World War. To my eight-year-old eyes it was an absolute revelation. The unflinching horror of war was laid bare – in a comic my parents could never have realised was so terrifying, stacked as it was alongside Whizzer and Chips, Nutty and the Beano. It kick-started a lifelong interest in history and comics, and over the last few years I’ve had the opportunity combine both those interests, working with schools and community groups to tell stories.

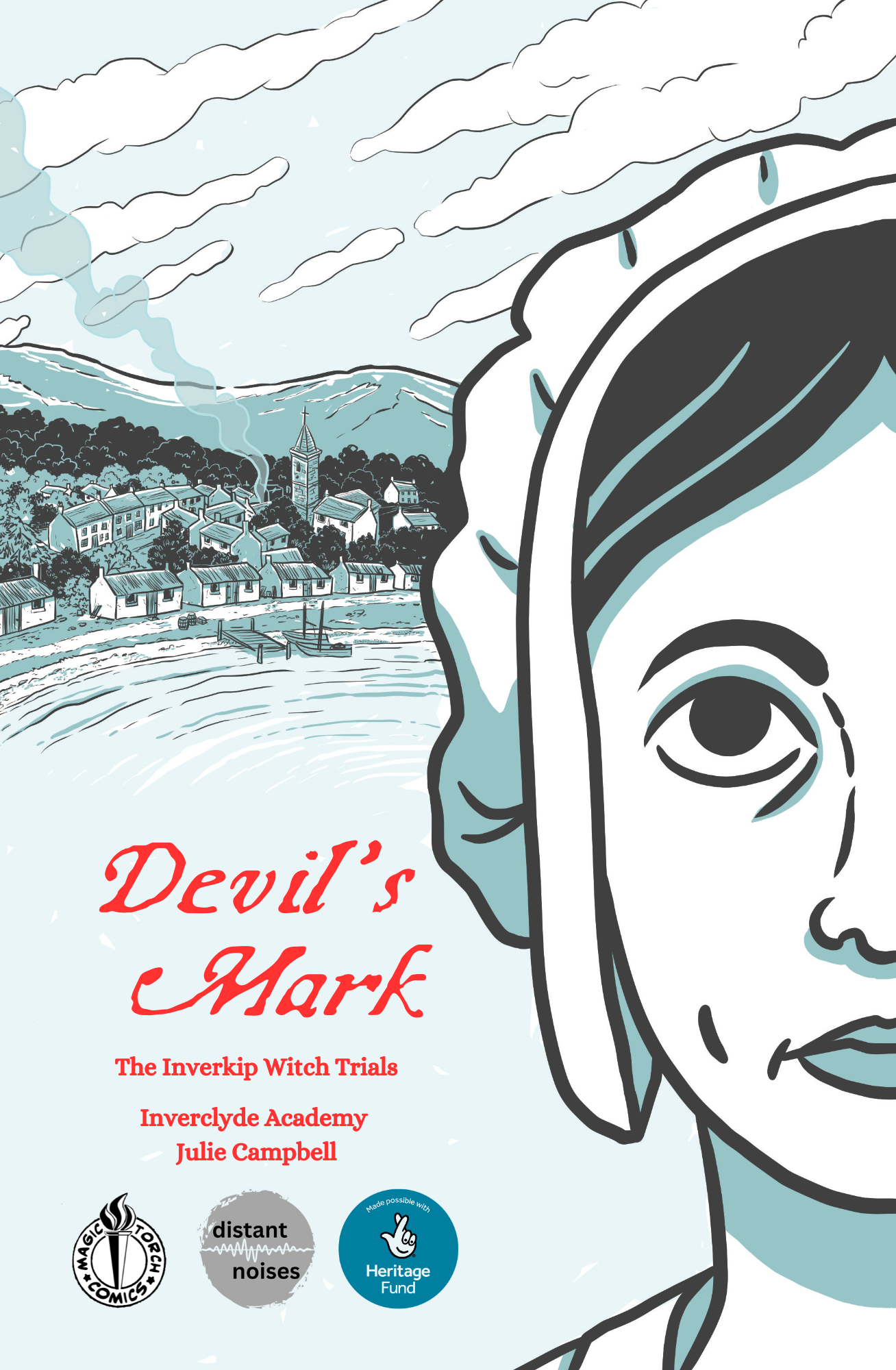

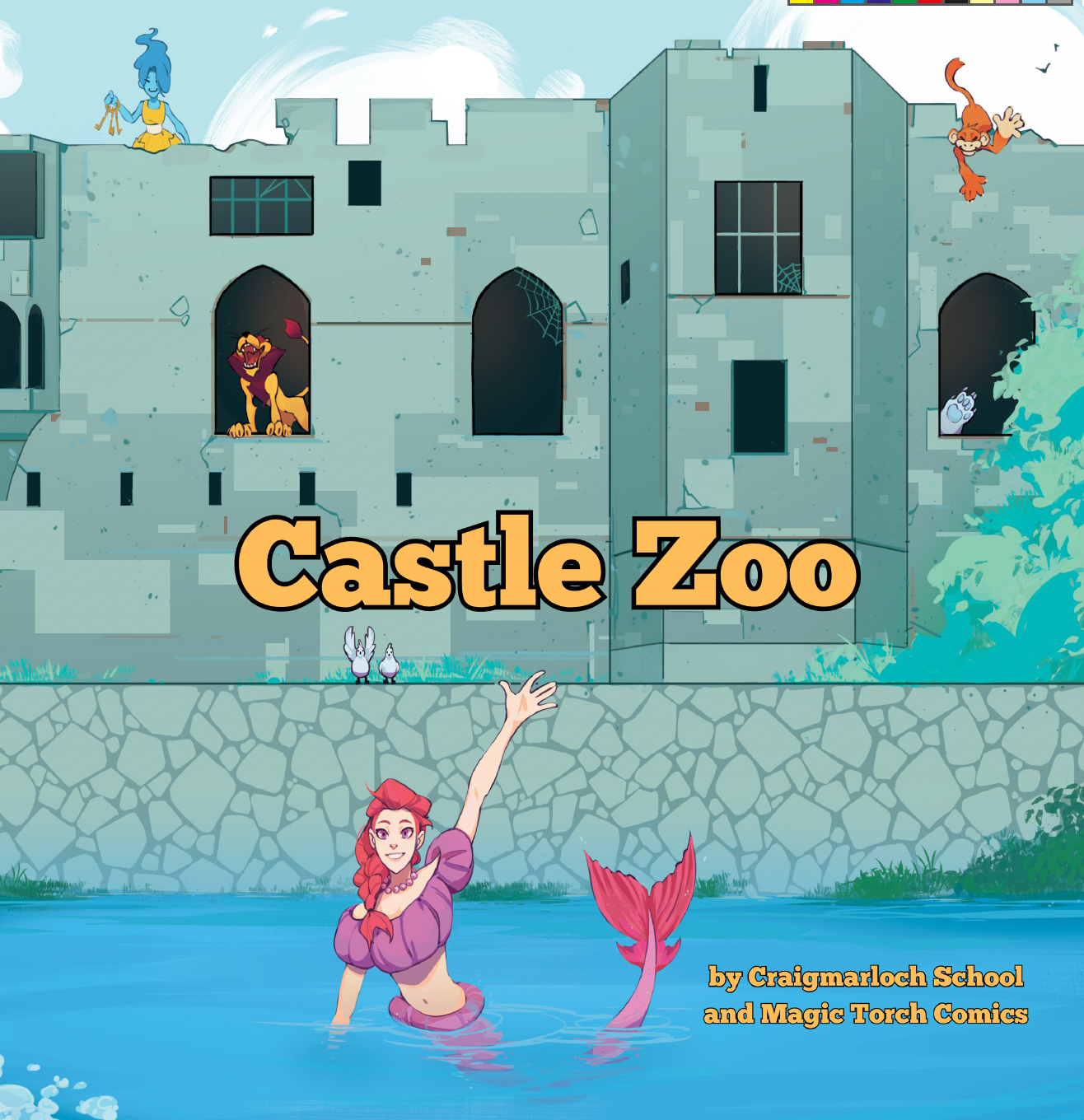

As part of an Inverclyde-based heritage group called Magic Torch, I’ve been involved in collecting and sharing stories since 1999. But it wasn’t until 2013 that we decided to use comics as a way of reaching new audiences. Inspired by the classic EC horror comics of the 1950s, we researched folktales and folklore from the area, filtering those old stories into the traditional grim “twist in the tale” strips. The resulting comic, Tales of The Oak, was released just in time for Hallowe’en. The title comes from our home town of Greenock, which is said to be named after the Green Oak Tree.

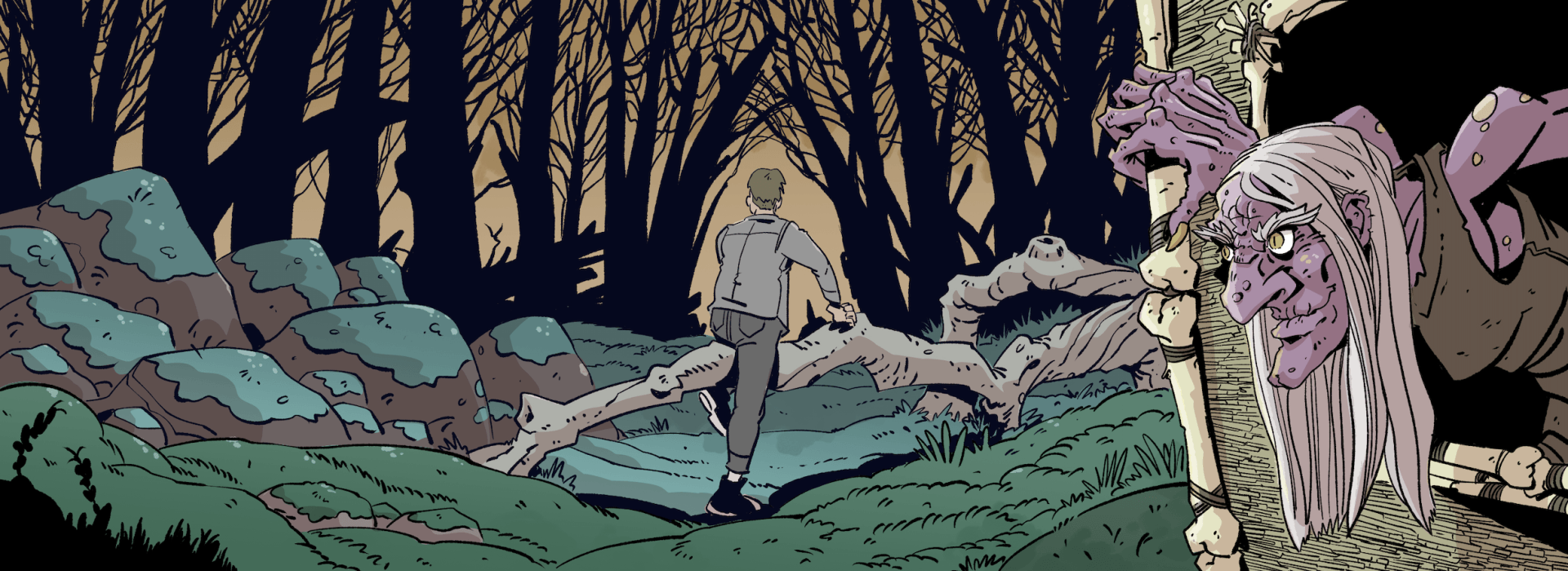

Our three hosts were straight out of local myth and legend: Auld Dunrod, a local landowner who was accused of witchcraft, Granny Kempock, a personification of a local standing stone, and Captain Kidd, a Scottish pirate who is claimed by both Greenock and Dundee. Tales of the Oak featured ghost stories, ballads, and urban legends – a particular favourite of mine is a bogeyman from the area, The Catman. Sightings and mentions of The Catman stretch back to the 1970s, all centred around a specific narrow lane connecting what was the industrial “East End” of the town to the town centre – one of those interesting crossing points at a self imposed division line, very often the focus for folklore and fairy stories. Throughout the boom years of shipbuilding, many local shipyards informally employed a “cat man”, someone who kept cats around the yards to keep rats at bay. The first mention of the vagrant Catman in Greenock coincides with the decline of the shipbuilding industry. Perhaps there is some connection. Regardless, what was striking when researching the folklore was how many of those stories were actually about the same thing: the urbanisation of places, or decay of old spaces.

Our next book, Achi Baba, explored the Gallipoli campaign, and in particular, a failed attempt on the hill of Achi Baba in which a local battalion, the 5th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, were involved. It was funded by Heritage Lottery through the Remembering the First World War fund.

Commemoration is of course a hugely political issue; even how you choose to react to remembrance can become a political act. We ended up a bit caught in the headlights on this point, as almost as soon as the grant was approved, we were suddenly unsure of how to approach the comic in a way that was respectful to the memories of those in the community, but without being jingoistic or celebratory. Ultimately, we chose to use words from those involved, letters home, poems, military records, war diaries, as varied a range of sources as we could find, threaded across the timeline of the campaign.

What struck us across all these sources was how the campaign at Gallipoli was so immediately associated with the battles of the Iliad thanks to geographic location of the battles. This association wasn’t attached retrospectively, with generals, academics and war poets packaging the campaign in these classical terms as it unfolded

Of course, it’s easy to argue that what we chose and how we presented it suggests an anti-war sentiment. Certainly, our artist did not shy away from more realistic depictions of death than might be found in Commando comics. Interestingly, this seems to have struck a chord with secondary school pupils and teachers – where it has found an audience beyond Inverclyde, in other schools across Scotland. In 2016, the book received the Community Archives and Heritage Group award for innovation.

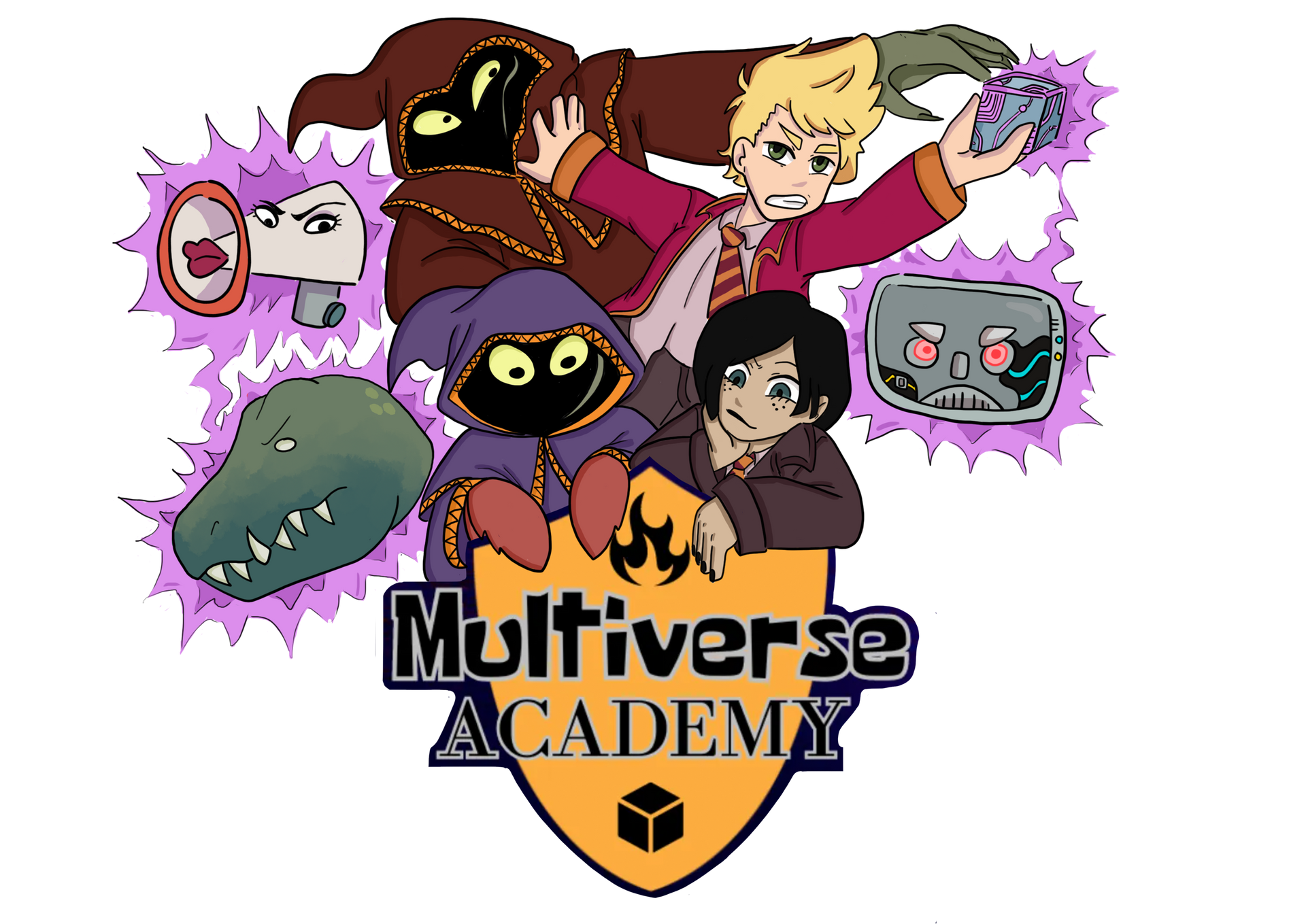

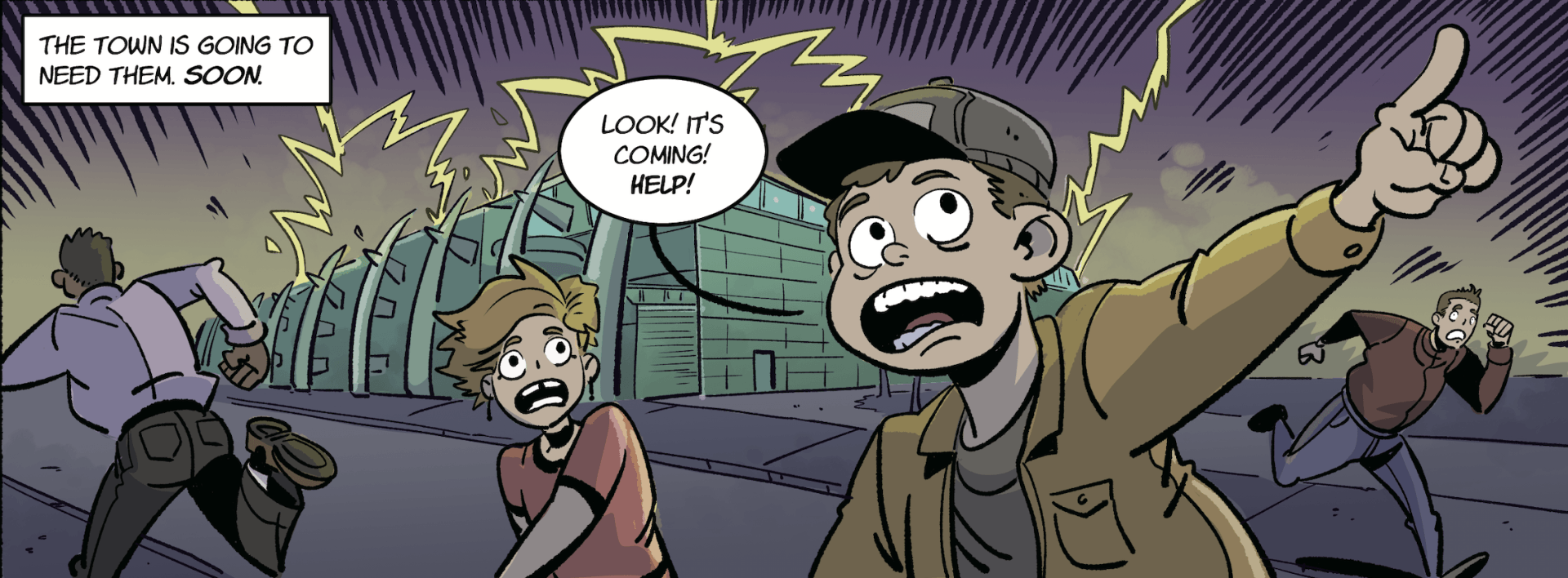

Over the last year, with the support of Firstport Scotland, our work has developed into a social enterprise. We have worked with schools to create comics that adapt the Gaelic songs of Mhairi Mhor nan Oran, explore the history of an old railway line and retell a tragic tale of young stowaways.We’ve also staged an exhibition in which 22 scenes from Scottish History were reimagined as classic comic covers. A historical comic strip even turned up in my first children’s book The Superpower Project, published by Kelpies last year. Upcoming projects include a comic for the Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology and I Thought I Was Undone, a graphic novel which explores the history and mystery of Captain William Kidd.

Art Spiegelman, the creator of Maus, a seminal graphic novel about the holocaust, famously describes comics as “the gateway drug to literacy” over the last two years in particular, our work has expanded to include running awareness raising sessions with schools and teachers to promote the ways in which historical comics can be used as texts in class. From Congressman John Lewis’s March, which explores the civil rights movement, to Marjane Satrapi’s autobiography Persepolis

about her experiences as young girl during the Islamic revolution in Iran, comics tackle a hugely diverse range of historical stories. And these stories have the power to engage new audiences not just in history, but in reading.

Perhaps we can help tell your story too.

Paul is more than happy to attend your meeting / event / conference to explore and explain his thoughts on comics, history and the work of Magic Torch - you can reach him via the contact form.

Artwork for Tales of the Oak and Achi Baba by Andy Lee

Artwork for The Stowaways and Stone of Destiny by Mhairi M Robertson

MTC Project Blog

Earlier this month, we were asked to produce some artwork for the Afrowegian Project , imagining an Afro-Futurist version of the story of real world cycling superhero, Marshall 'Major' Taylor. The comic display panels form part of an exhibition by the riverside in Glasgow throughout October. You can read more about the work of the project and how to get involved. We're looking forward to doing some more collaborative work with Afrowegian's Jim Muotone, down in Inverclyde over the next few months.